Last week I posted the first part of my review of the massive volume, The Enduring Authority of the Christian Scriptures, edited by D.A. Carson. This week we’ll cover what I consider some significant weaknesses along with some brief concluding remarks.

And now the negatives

There are several essays that are particularly weak, either because they seem to beg the question or their arguments don’t hold up well under the weight of the evidence. I was a bit surprised given the intellectual gravitas represented by the authors in this volume, that several of them were of such mediocre quality. This part of the review will highlight four of them: Carson’s Introduction, Dempster’s essay on The Old Testament Canon, Waltke’s essay on Myth, History and the Bible, and Birkett’s essay on Science and Scripture.

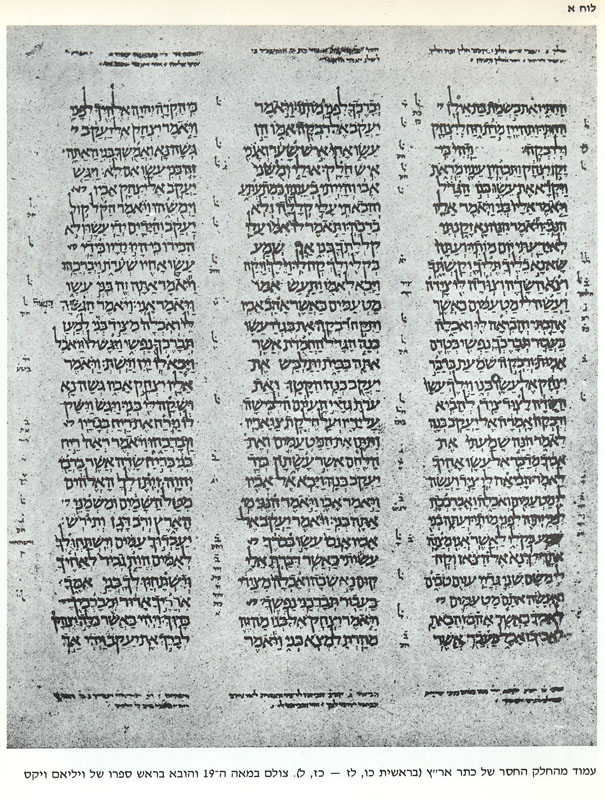

We will begin with Steven G. Dempster’s chapter, “The Old Testament Canon, Josephus, and Cognitive Environment,” in which he seeks to demonstrate that a canon of books was well known and closed at the time of Josephus and that it had been so for quite some time. He calls the position of those who think the Jewish canon was not set until the second century CE and that the Christian canon until even later, minimalism. This in itself is an interesting choice of words, since that term is usually used (pejoratively) of those who think the biblical books largely lack historical usefulness by those who think otherwise (so-called maximalists). His contention is that the lack of (written) evidence for a well defined canon of books in the first and second centuries actually points to the idea that the issue wasn’t a concern because it was already settled. While this may look suspiciously like an argument from silence, he cites Josephus in Against Apion (8:37-43), to point out that Josephus explicitly asserted that there were 22 books in the Jewish canon, five of Moses, 13 books from Moses to Artaxerxes, and four books containing hymns and precepts for living (10224-10242).

Dempster draws the conclusion that this list is canonical, that it limits the scope of canonical works to a particular time (no later than the Persian period) and that the canon was clearly enumerated and already divided into three sections (10248). He argues against several scholars who advocate that Josephus’ choice of books was “reflecting the gradual emergence of a small circle of Pharisees” (10295) because if that were the case, Josephus would forfeit his credibility. This of course, seems to ignore that for Josephus’ broader project, credibility was about making the Jews look good, especially to the elites in the Roman empire. He does so here by pointing to both the antiquity of the Jewish books and their much more manageable number. Dempster goes on to note that in 4 Ezra, a work contemporaneous with Josephus’, it states that there are also 22 books. He then helpfully gives several citations of early works, from the Babylonian Talmud, with 24, to Bishop Melito, who mentions 25. To defend the books that Melito enumerates, Dempster considers the omission of the book of Esther accidental. This, of course, is hardly likely, given that Esther was not found at Qumran either, making it clear that this book was on the periphery of canon, at best.

This highlights the broader problem with Dempster’s assertion of a fixed canon by the time of Josephus. Even from his own evidence, it appears that the lists of sacred books he references are at best a centered set, not a bounded set. By this I mean that there were books that were considered at the core of the scriptures by virtually all Jewish groups. This would obviously include the Pentateuch, which was even acknowledged by the Samaritans (in their own redaction, of course) and likely included almost all of the books we number among the prophets as well. But the rest of the books, which later became known as the Writings, were much less definitive (Sidnie White Crawford. Rewriting Scripture in Second Temple Times, 113). So which particular books belonged to the overall list of sacred books was not so well enumerated because they were not so well defined. And if, by definition, a canon is a closed set (Ulrich, The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Origins of the Bible, p57; Metzger, Canon of the New Testament, p7), then as much as Dempster may believe that Josephus had a canon that was representative of the broader contemporary Jewish community, the evidence does not appear to support this. The mere fact that the number of books was in flux shows that a canon was, at best, specific to particular communities. For example, we see that at Qumran, 1 Enoch and Jubilees appear to have been considered scriptural and there is a possibility of others (White Crawford, 146).

Dempster’s defense of a Canonical Epoch is pretty traditional, following Josephus’ testimony, which has the closing of the canonical epoch with Artaxerxes. Here, Dempster attempts to separate a form of prophecy that was common, such as with the high priest, John Hyrcanus mentioned in 1 Maccabees, from a form of prophecy that led to scriptural writings. Dempster also cites 1 Maccabees as evidence that prophecy had ceased from Ezra-Nehemiah onward, although in truth, at least two of his citation (4:45-46 and 14:41) could be interpreted to imply that there was an expectation that prophets would come in the foreseeable future. This is not to say that the mainstream consensus wasn’t that prophecy was disappearing from Israel, at least as advocated by those in positions of power. That does indeed appear to be the case. But it’s possible that treating prophecy as coming to an end in the Persian period legitimized the Hasmonean endeavor, at least in part, by positioning themselves as the saviors of Israel’s heritage (Carr, 158-59). Other data from Qumran, as we saw above, shows that later works were considered scriptural for that community and that they functioned with a belief in active prophecy, as did the early Christian movement. (At this point, I’d like to see research regarding the role of prophecy among marginalized groups in the second temple period, but that’s a different issue.)

One of the reasons that prophecy ending with Ezra-Nehemiah is important for Dempster’s argument is that Daniel is widely considered among modern scholars to stem from the Maccabean period. To his credit, he acknowledges this and that scholars see an uncanny similarity in the prophecies portrayed in Daniel to the events leading up to just prior to the death of Antioches IV Epiphanes. But his response is to simply wave it off.

The only difficulty with this interpretation is that one must conclude that, unlike all the other pseudonymous works that claimed an ancient, canonical pedigree, the book of Daniel “fooled” everyone and made it into the canon! (10647-10649).

That isn’t actually an answer. It ignores that some groups did indeed treat particular pseudonymous books as Scripture (including, at least a bit later, Christians!) and that many of the books may have had their last major revision during the Maccabean period as part of the process of centralizing books (technically, scrolls) containing important traditions for Jewish self-understanding. 2 Maccabees states that during this period, Judas Maccabaeus “collected all the books that had been lost on account of the war” (2 Macc 2:14). However, this is almost assuredly not just the collection of ancient works considering that the multiple books of the Maccabees were also written during this time, but likewise, the formation and/or redaction of many. So to state that Daniel would’ve had to have “fooled” everybody else cannot be sustained in light of the evidence.

Throughout the chapter, it seems surprising how much weight Dempster gives to Josephus and other late evidence over against what was found in Qumran. “If this textual pluriformity at Qumran provides a window into the wider Jewish world, it seems to suggest that Josephus’s view of the canonical text is totally out of touch with reality” (10794-10795). But while “this may be something of a hard intellectual pill to swallow” (10801-10802), the evidence does indeed appear to support that Josephus provides only a single data point, albeit one that eventually grew to become the majority. Even as far as Josephus is concerned, it is likely that the actual texts he was using were at times at variance with the Masoretic Text we now have, what Dempster sees as a sort of majority text. For instance, Ulrich argues that Josephus uses a text for 1-2 Samuel that most closely resembles 4QSama (Q), a text that does not agree with the Masoretic Text (MT). There are “at least four readings in which the biblical scroll use by J [Josephus] agrees with Q against MT, but no reading emerge in which J agrees with MT against Q” (Ulrich, The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Origins of the Bible, p186). So it would appear that “Josephus’s claim that nothing had been added or subtracted from the biblical texts was not hyperbole” (10845-10846) is unsustainable, even as witnessed by Josephus use of variant text forms himself. (Assuming the manuscripts of Josephus we have were not revised at some point as well. Cf. Karen H. Jobes, Invitation to the Septuagint, pps 283-84 n33).

We have gone on much too long already in reviewing this particular essay, but that’s largely because it requires some of the most detailed reasoning to understand its faults. If nothing else, it highlights that the same evidence can be interpreted multiple ways. On the positive side, this is one of the few essays in the book that acknowledges some of the textual difficulties, especially of the Hebrew Scriptures. But I wish that significant scholarly research had been better engaged and not simply brushed aside with the wave of a rhetorical hand.

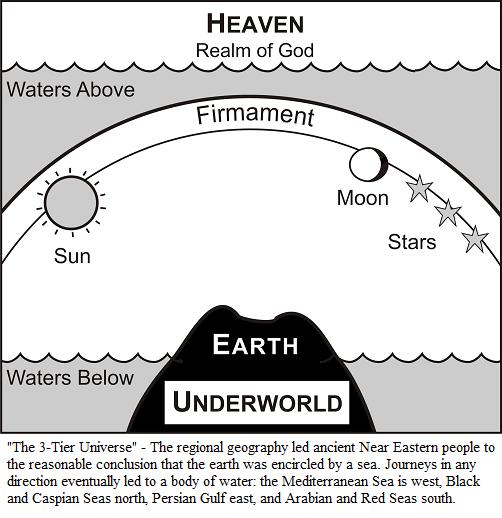

I found Waltke’s essay, “Myth, History and the Bible,” particularly unpersuasive in large part because its reasoning seems to beg the questions. He defines myth as fundamentally ahistorical, which I would agree with in general, although this needs fleshing out, as well as “a story informed by pantheism and magic” (17015), which seems to predetermine where he wants his argument to go. Methodologically, Waltke is attempting to classify texts along the same lines a biologist would classify organisms; kingdom, phylum, genus, etc… with the goal that myth be defined more narrowly. It’s an interesting approach and he looks at several ancient Mesopotamian myths to tease out the difference between them and the Bible. But his definition of myth as innately tied to pantheism exposes a predefined bias for the Bible being of a completely different category than other ancient writings. His definition of myth can be contradicted by several examples of modern day myths that do not fall in this category, whether the myth of George Washington chopping down the cherry tree or, possibly a bit more controversially, the myth of redemptive violence so popular in our culture. In both cases, there is nothing pantheistic or magical about them! Even if we grant ancient myth is necessarily referring to the supernatural and ahistorical, it’s hard to understand why Genesis 1-11 would not qualify, given typical ancient mythical markers of heroes from days gone by, extraordinarily long lives and even an unusual beast, in the form of a talking serpent. However, for some reason he classifies the Bible as poetic history because he believes it is anchored in history but the tale of Gilgamesh as myth because he does not. Of course, given that the Sumerian King List includes Gilgamesh, it appears that the Akkadian epic would likely have been considered in the genus, to use Waltke’s categories, historio-poesis. And this is the overall weakness of this essay. It continually privileges the biblical text. Nowhere is this clearer than in the conclusion, where he states, “the Mesopotamian myths bastardize the historical reality, which the Bible preserves in pure form” (17782-17783). It is fine to make this assertion from a confessional point of view, but it does not hold much weight in a volume meant to employ scholarly approaches to the Bible. In part, this is disappointing because it overshadows some very interesting work where Walke helpfully addresses how ancient Israelite writers borrowed Canaanite imagery but not necessarily the associated theology, concepts also mentioned by others, such as in Robert Alter’s, The Five Books of Moses (cf. p425 n16), but very clearly articulated here.

We will now move on to look at Kirsten Birkett’s chapter, “Science and Scripture.” I had high hopes for this essay, as the interplay between what we know (epistemology) and science in how we understand scripture is an important subject. She first argues that in the case of Galileo, the problem was that the church was too pro-science, not that it was anti science. This is an interesting perspective and to a degree I find her argument persuasive, although the subheading seems to overstate her case. Her contention is that the church had bought into the science of its day, a form of geocentrism derived from Aristotelian physics. At least since Thomas Aquinas tied the beliefs of the church to an Aristotelian framework, “to question Aristotle was to question theology” (29189). She uses this fascinating tale to present her central argument, that “Christians should never allow Christianity to be tied to a secular system of thought” (29258). She then goes on to discuss different ways the age of the earth has been understood through Church history. Interestingly, she cautions not just against a scientific reading of Genesis, but also against the rise of creationism, saying “interpretation in reaction can be just as problematical as interpretation in accordance with science” (29409-29410). Finally, she goes on to discuss models for how science can interact with Scripture, focusing primarily on Denis Alexander, John Polkinghorne, and to a lesser extent, Arthur Peacock, finding all three have “not let Scripture guide his science, but science guide his reading of Scripture” since they “simply go against Scripture” (299913-29915). This is because all three, to one degree or another, let science influence or determine how scripture should be understood and what the God in those Scriptures can and cannot do. Using the grid of science these three assert God cannot do things that are logically or scientifically self-contradictory. Yet for Birkett, this restricts God because “God is clearly described in the Bible as sovereign, and predetermining; he not only knows what happens in the future, but he makes it happen” (29915-29916). For Birkett the problem is that they interpret scripture using systems from outside scripture. “External philosophies, even ones as successful in explanatory power as modern science, do not have the final say” (29934-29935). Of course, what boarders on ironic here is that her reading of scripture seems to be through a distinctly Reformed lens, with it’s focus on “God’s sovereignty and divine freedom” (29937). Doubtless, she would claim that this is derived from scripture itself but that’s also how Aquinas understood his work.

In essence, it appears that Birkett is advocating that we read the Bible from some detached position, unaffected by what we learn from outside the Bible, something that I don’t know how to do and seriously doubt is even possible, given our own situatedness. What makes this essay ultimately unsatisfying is that it never gives any examples of what it would look like to do this. For a rather trivial example, science tells us that the mustard seed is not the smallest seed. Should we believe the Bible when Jesus says that the mustard seed is the smallest seed on earth (Mark 4:31)? Obviously, Genesis 1 is far more important, but why should we allow science to change how we think of Mark 4:31 and not Genesis? This is the question left unanswered in the essay and why this essay is ultimately unsatisfying.

We will conclude this review, rather paradoxically, with D. A. Carson’s extended Introduction, which serves as both a literature review as well as an introduction to the present work, with his own concerns sprinkled in. One would hope that in the introduction to a volume that seeks to provide a solid intellectual foundation for both the authority of Scripture and ultimately, its inerrancy, that the introduction would reflect sound academics and a thorough understanding of the essays within it. Unfortunately, it does neither. Carson steers into ad hominem attacks at times, referring to Stephen L Young’s essay as being “snide” (474) as well as Kenton L Sparks and Peter E. Enns as “both slightly angry and slightly self-righteous” (565-566). He criticizes J. R. Daniel Kirk for saying “that an inerrantist must hold to a young earth” (913), yet ignoring that the CSBI, as we have seen, virtually requires it (a document he himself has signed, mind you). He also displays the virtually de rigueur conservative Protestant misrepresentation of Catholic teaching, stating that inerrancy is less of a problem for Catholics because for them “the ultimate teaching authority is not Scripture” (897). The irony, as we have seen, is that the essay that he sites within this very volume clearly states otherwise.

In his discussion of Carlos Bovell’s work, Carson conflates, as do many of the authors in the book, high views of Scripture with inerrancy. For example, he states that we find high views of scripture across “many philosophical and theological contexts” (1078) followed by criticizing Bovell for condemning “inerrancy for its (ostensible) dependence on Cartesian foundationalism” (1084-1085), thereby tying a high view of Scripture and its authority inextricably to inerrancy. Yet, as Rea’s essay points out, this is not necessarily the case. And finally, he brings up the classic bugaboo that “We need to adopt a certain cautious skepticism … regarding some of the claims of science” (1133-1134), although to his credit, he does say that this shouldn’t “sanction arrogant dismissal” (1145-1146) of it. It’s unfortunate because he sets up a type of Christian certainty against the provisional nature of science. However, this overlooks two things: First, as the essay by Vanhoozer notes, Christian Doctrine is also provisional and second, by the very nature of science, it is self correcting. Given the understanding of Scripture advocated in this essay, could the same be said about Christianity?

Conclusion

I found this book to be surprisingly helpful in several ways, albeit, perhaps not in the way the editor may have intended. Principally, it demonstrates, however unwittingly, that academics are starting to move beyond the definition of inerrancy asserted in the CSBI and at the same time, lays some of the theological and philosophical groundwork on how this might be done, while still maintaining what it considers the essential doctrine of inerrancy. It was helpful to include a section on world religions, given our highly connected and at times, politically charged world. I felt Glaser’s essay in this section did an excellent job of introducing the reader to some of the similarities and broad differences in how Muslims understand the Qur’an compared to how Christians understand the Bible. (I do not feel qualified to speak to the other essays in that section.) Unfortunately, as large works like this are wont to experience, the quality of the essays varies dramatically overall. Most disappointing, though, is what is missing: a rigorous look at the nature of Scripture given the biblical, archeological, linguistic and textual evidence available to us today. Instead, a predetermined answer is assumed rather than critically explored and developed.

What about you? What’s at stake in how science and Scripture might interact? Do you think that the Bible deserves a privileged position in terms of treating it as history as compared to myth?

The Enduring Authority of the Christian Scriptures (Edited by D.A. Carson. Grand Rapids, Michigan : Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2016) sets out to provide, in one rather large volume (over 1200 pages!), a defense of, not so much the authority of the Christian Scriptures, but of their inerrancy. The book contains numerous essays on Historical, Biblical, Theological, Philosophical and Epistemological topics, along with a handful of essays regarding Comparative Religions as it relates to the authority of the Bible. In the introduction, which in itself contains a wonderful bibliography of non inerrantists’ works, the editor, D. A. Carson, surveys a wide variety of fairly recent (and some not so recent) monographs on the nature of the Bible. His overarching concern seems to be that these recent works “go beyond” the fundamentals of the doctrine of scripture and “for better or for worse, break fresh ground” (Kindle location 383; all locations are Kindle locations unless otherwise noted), which I take to mean denying inerrancy.

The Enduring Authority of the Christian Scriptures (Edited by D.A. Carson. Grand Rapids, Michigan : Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2016) sets out to provide, in one rather large volume (over 1200 pages!), a defense of, not so much the authority of the Christian Scriptures, but of their inerrancy. The book contains numerous essays on Historical, Biblical, Theological, Philosophical and Epistemological topics, along with a handful of essays regarding Comparative Religions as it relates to the authority of the Bible. In the introduction, which in itself contains a wonderful bibliography of non inerrantists’ works, the editor, D. A. Carson, surveys a wide variety of fairly recent (and some not so recent) monographs on the nature of the Bible. His overarching concern seems to be that these recent works “go beyond” the fundamentals of the doctrine of scripture and “for better or for worse, break fresh ground” (Kindle location 383; all locations are Kindle locations unless otherwise noted), which I take to mean denying inerrancy.

![See page for author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons damascus_pentateuch](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1d/Damascus_Pentateuch.png)